> MindXO Insight | Analysis

Based on more than 1,200 reported AI incidents analyzed by MIT, this article examines how AI risks actually emerge in organizational settings.

The findings show that most incidents are socio-technical, occur after deployment, and concentrate in a limited number of impact domains, challenging static or compliance-only approaches.

Building on these insights, the article argues for proactive, lifecycle-based AI risk management and a clear distinction between system-level and organization-wide risks.

A one-page operating model clarifying the distinct roles of AI governance, risk management, and compliance across the AI lifecycle.

→ Download the ModelMindXO AI Risk Quadrant

Over the past two years, “AI risk” has become a ubiquitous expression. It appears in board presentations, regulatory consultations, strategy decks, and media headlines.

Depending on who is speaking, “AI risk” can refer to hallucinations in chatbots, biased credit decisions, intellectual property leakage, large-scale misinformation, or even existential threats. These concerns are all legitimate, but they differ fundamentally in nature, origin, and mode of manifestation.

When a single label is used to describe such a wide range of phenomena, it becomes difficult to reason about risk in a disciplined way, let alone govern it.

This confusion is not accidental. It reflects years of parallel work across academia, industry, and policy, each approaching AI risk from different angles and with different objectives.

To address this, a large research effort led by MIT researchers undertook a systematic review of existing AI risk frameworks and real-world AI incidents.

The MIT AI Risk Repository synthesizes over 1,200 reported AI incidents and more than 2,000 distinct AI risks extracted from hundreds of academic, industry, and policy sources.

The central finding is simple but powerful. AI risks must be understood through distinct lenses, and confusion arises when these lenses are collapsed into a single taxonomy.

MIT distinguishes between: 1- how AI risks emerge; and 2- what kinds of harm they produce.

The first lens focuses on causality. It asks questions such as:

- Who or what caused the risk to emerge, a human actor, an AI system, or external conditions?

- Was the outcome intentional or accidental? Did the risk arise before deployment, or only once the system was in operational use?

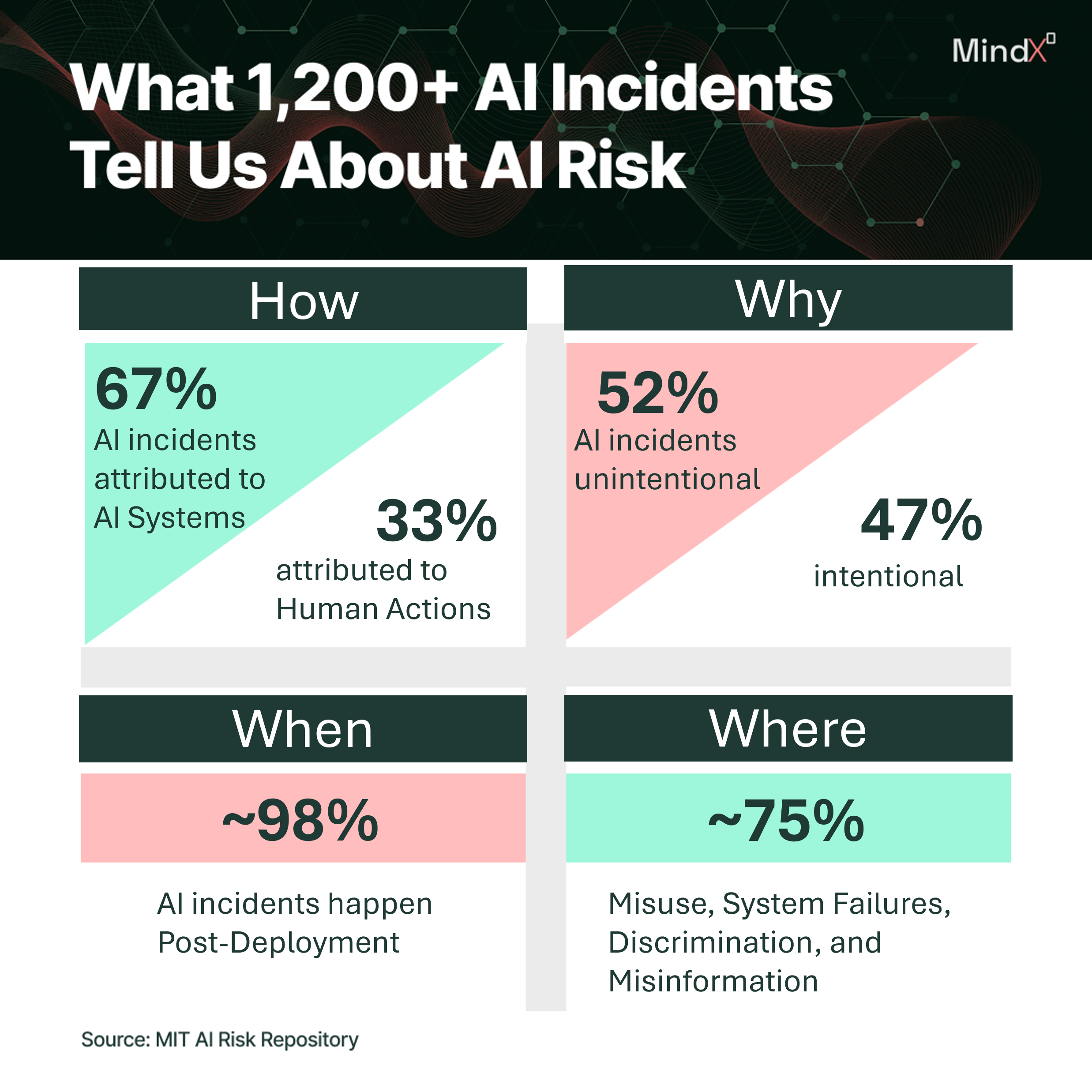

This lens is concerned with how a risk comes into existence. It mirrors approaches used in other safety-critical domains, where understanding causation is essential for accountability and prevention. According to the MIT repository:

- Approximately 67% of reported AI incidents are attributed primarily to AI system behavior,

- Around 33% are attributed to human actions,

- With a small residual category for ambiguous cases.

Crucially, this does not imply autonomous AI agency. It highlights the socio-technical nature of AI risk, where system behavior reflects upstream human decisions in design, training, configuration, and deployment interacting with real-world environments.

AI incidents are almost evenly split between intentional and unintentional outcomes. Roughly half result from deliberate misuse, while the other half arise unintentionally through system behavior, misalignment, or unforeseen interactions. This balance reinforces the need for governance approaches that address both malicious use and ordinary operational drift.

Timing further sharpens this insight. Roughly 97.5% of reported AI incidents occur post-deployment, with fewer than 3%identified before systems are in live use. This suggests that AI risk is overwhelmingly an operational phenomenon, not merely a design-time concern

The second lens focuses on impact domains. It classifies risks according to the type of harm they produce, such as discrimination, misinformation, system safety failures, privacy violations, or broader societal effects.

Here again, the MIT data provides useful signals. Reported AI incidents are highly concentrated. About 75% of documented incidents fall into just four domains:

- Malicious use of AI systems (approximately 34%),

- AI system safety failures and limitations (approximately 23%),

- Discrimination and toxicity (approximately 19%),

- Misinformation (approximately 13%).

Other domains, such as privacy and security, human–computer interaction issues, or socioeconomic and environmental harms, account for a much smaller share of reported incidents.

This concentration should not be interpreted as a ranking of importance. Rather, it reflects where AI systems are currently most exposed, at scale, in open environments, and in direct interaction with users.

The key point MIT makes is that causal explanations and impact domains serve different purposes. Saying “bias risk” does not explain how the risk emerged, just as describing a failure as accidental does not explain who or what was harmed.

When AI risks are treated as a monolithic block, organizations often end up with long, overlapping risk lists, unclear ownership, and governance mechanisms that are either excessively heavy or dangerously superficial.

The MIT AI Risk Repository’s empirical findings point to clear implications for how organizations should govern and manage risks.

First, the near-even split between intentional and unintentional incidents fundamentally challenges reactive approaches to AI risk.

Roughly half of reported AI incidents result from deliberate misuse, while the other half arise unintentionally through system behavior, misalignment, or unforeseen interactions. This balance makes it clear that AI risk cannot be addressed solely through post-incident response or misuse prevention.

Organizations must invest in proactive governance and risk management capable of anticipating both malicious use and ordinary operational drift.

Second, the distribution of incident sources highlights the need to distinguish between system-level and organization-wide risks.

Approximately 67% of reported incidents are attributed primarily to AI system behavior, while 33% are attributed to human actions. These two sources of risk call for different mitigation strategies and different governance owners:

- System-level risks require technical controls, testing, monitoring, and lifecycle gates tied to specific AI systems.

- Organization-wide risks require policies, training, access controls, and cultural safeguards that shape how humans interact with AI tools.

Treating these risks as a single category leads to blurred accountability and ineffective controls.

Third, the timing of incidents reinforces the centrality of lifecycle-based governance.

With more than 97% of reported AI incidents occurring after deployment, AI risk emerges overwhelmingly during real-world operation rather than at design time. This finding directly challenges governance models that concentrate controls upstream and relax oversight once systems are live.

Effective AI risk management must therefore extend across the full AI system lifecycle, with particular emphasis on continuous monitoring, feedback loops, and periodic reassessment once systems are deployed and scaled.

Taken together, these findings point to a clear conclusion. AI governance is not a static compliance exercise, nor a one-time design review. It is an ongoing risk management discipline that must be proactive rather than reactive, differentiated rather than monolithic, and operational rather than purely procedural.

The MIT work provides the analytical clarity to reach this conclusion. The remaining challenge for organizations is to translate that clarity into governance structures, controls, and decision processes that reflect how AI risks actually materialize in practice.

The rapid spread of AI has outpaced our collective ability to talk about its risks clearly. MIT’s work demonstrates that clarity is possible, not by simplifying AI risks into a single narrative, but by acknowledging their multidimensional nature.

AI risk is not unknowable, nor does it require reinventing risk management. It follows familiar logic, events, probabilities, and impacts. What has been missing is a shared structure.

By restoring that structure, the MIT AI Risk Repository makes AI risk governable again and provides a foundation for organizations to move from anxiety to informed decision-making.

To help organisations navigate these concepts, we’ve created a one-page operating model clarifying the distinct roles of AI governance, risk management, and compliance across the AI lifecycle..

A one-page guide to help organisations distinguish principles, practices, and governance in AI initiatives.

→ Download the Model